Guest Post: How Hyperinflation Will Happen

- Ben Bernanke

- CPI

- CRAP

- Exchange Traded Fund

- Fail

- Federal Reserve

- Government Stimulus

- Gross Domestic Product

- Guest Post

- Hyperinflation

- Japan

- Main Street

- Nationalization

- New Normal

- Purchasing Power

- Quantitative Easing

- Real estate

- recovery

- Smart Money

- Sovereign Debt

- Too Big To Fail

- Unemployment

Submitted by Gonzalo Lira

How Hyperinflation Will Happen

Right now, we are in the middle of deflation. The Global Depression we are experiencing has squeezed both aggregate demand levels and aggregate asset prices as never before. Since the credit crunch of September 2008, the U.S. and world economies have been slowly circling the deflationary drain.

To counter this, the U.S. government has been running massive deficits, as it seeks to prop up aggregate demand levels by way of fiscal “stimulus” spending—the classic Keynesian move, the same old prescription since donkey’s ears.

But the stimulus, apart from being slow and inefficient, has simply not been enough to offset the fall in consumer spending.

For its part, the Federal Reserve has been busy propping up all assets—including Treasuries—by way of “quantitative easing”.

The Fed is terrified of the U.S. economy falling into a deflationary death-spiral: Lack of liquidity, leading to lower prices, leading to unemployment, leading to lower consumption, leading to still lower prices, the entire economy grinding down to a halt. So the Fed has bought up assets of all kinds, in order to inject liquidity into the system, and bouy asset price levels so as to prevent this deflationary deep-freeze—and will continue to do so. After all, when your only tool is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

But this Fed policy—call it “money-printing”, call it “liquidity injections”, call it “asset price stabilization”—has been overwhelmed by the credit contraction. Just as the Federal government has been unable to fill in the fall in aggregate demand by way of stimulus, the Fed has expanded its balance sheet from some $900 billion in the Fall of ’08, to about $2.3 trillion today—but that additional $1.4 trillion has been no match for the loss of credit. At best, the Fed has been able to alleviate the worst effects of the deflation—it certainly has not turned the deflationary environment into anything resembling inflation.

Yields are low, unemployment up, CPI numbers are down (and under some metrics, negative)—in short, everything screams “deflation”.

Therefore, the notion of talking about hyperinflation now, in this current macro-economic environment, would seem . . . well . . . crazy. Right?

Wrong: I would argue that the next step down in this world-historical Global Depression which we are experiencing will be hyperinflation.

Most people dismiss the very notion of hyperinflation occurring in the United States as something only tin-foil hatters, gold-bugs, and Right-wing survivalists drool about. In fact, most sensible people don’t even bother arguing the issue at all—everyone knows that only fools bother arguing with a bigger fool.

A minority, though—and God bless ’em—actually do go ahead and go through the motions of talking to the crazies ranting about hyperinflation. These amiable souls diligently point out that in a deflationary environment—where commodity prices are more or less stable, there are downward pressures on wages, asset prices are falling, and credit markets are shrinking—inflation is impossible. Therefore, hyperinflation is even more impossible.

This outlook seems sensible—if we fall for the trap of thinking that hyperinflation is an extention of inflation. If we think that hyperinflation is simply inflation on steroids—inflation-plus—inflation with balls—then it would seem to be the case that, in our current deflationary economic environment, hyperinflation is not simply a long way off, but flat-out ridiculous.

But hyperinflation is not an extension or amplification of inflation. Inflation and hyperinflation are two very distinct animals. They look the same—because in both cases, the currency loses its purchasing power—but they are not the same.

Inflation is when the economy overheats: It’s when an economy’s consumables (labor and commodities) are so in-demand because of economic growth, coupled with an expansionist credit environment, that the consumables rise in price. This forces all goods and services to rise in price as well, so that producers can keep up with costs. It is essentially a demand-driven phenomena.

Hyperinflation is the loss of faith in the currency. Prices rise in a hyperinflationary environment just like in an inflationary environment, but they rise not because people want more money for their labor or for commodities, but because people are trying to get out of the currency. It’s not that they want more money—they want less of the currency: So they will pay anything for a good which is not the currency.

Right now, the U.S. government is indebted to about 100% of GDP, with a yearly fiscal deficit of about 10% of GDP, and no end in sight. For its part, the Federal Reserve is purchasing Treasuries, in order to finance the fiscal shortfall, both directly (the recently unveiled QE-lite) and indirectly (through the Too Big To Fail banks). The Fed is satisfying two objectives: One, supporting the government in its efforts to maintain aggregate demand levels, and two, supporting asset prices, and thereby prevent further deflationary erosion. The Fed is calculating that either path—increase in aggregate demand levels or increase in aggregate asset values—leads to the same thing: A recovery in the economy.

This recovery is not going to happen—that’s the news we’ve been getting as of late. Amid all this hopeful talk about “avoiding a double-dip”, it turns out that we didn’t avoid a double-dip—we never really managed to claw our way out of the first dip. No matter all the stimulus, no matter all the alphabet-soup liquidity windows over the past 2 years, the inescapable fact is that the economy has been—and is headed—down.

But both the Federal government and the Federal Reserve are hell-bent on using the same old tired tools to “fix the economy”—stimulus on the one hand, liquidity injections on the other. (See my discussion of The Deficit here.)

It’s those very fixes that are pulling us closer to the edge. Why? Because the economy is in no better shape than it was in September 2008—and both the Federal Reserve and the Federal government have shot their wad. They got nothin’ left, after trillions in stimulus and trillions more in balance sheet expansion—

—but they have accomplished one thing: They have undermined Treasuries. These policies have turned Treasuries into the spit-and-baling wire of the U.S. financial system—they are literally the only things holding the whole economy together.

In other words, Treasuries are now the New and Improved Toxic Asset. Everyone knows that they are overvalued, everyone knows their yields are absurd—yet everyone tiptoes around that truth as delicately as if it were a bomb. Which is actually what it is.

So this is how hyperinflation will happen:

One day—when nothing much is going on in the markets, but general nervousness is running like a low-grade fever (as has been the case for a while now)—there will be a commodities burp: A slight but sudden rise in the price of a necessary commodity, such as oil.

This will jiggle Treasury yields, as asset managers will reduce their Treasury allocations, and go into the pressured commodity, in order to catch a profit. (Actually it won’t even be the asset managers—it will be their programmed trades.) These asset managers will sell Treasuries because, effectively, it’s become the principal asset they have to sell.

It won’t be the volume of the sell-off that will pique Bernanke and the drones at the Fed—it will be the timing. It’ll happen right before a largish Treasury auction. So Bernanke and the Fed will buy Treasuries, in an effort to counteract the sell-off and maintain low yields—they want to maintain low yields in order to discourage deflation. But they’ll also want to keep the Treasury cheaply funded. QE-lite has already set the stage for direct Fed buys of Treasuries. The world didn’t end. So the Fed will feel confident as it moves forward and nips this Treasury yield jiggle in the bud.

The Fed’s buying of Treasuries will occur in such a way that it will encourage asset managers to dump even more Treasuries into the Fed’s waiting arms. This dumping of Treasuries won’t be out of fear, at least not initially. Most likely, in the first 15 minutes or so of this event, the sell-off in Treasuries will be orderly, and carried out with the idea (at the time) of picking up those selfsame Treasuries a bit cheaper down the line.

However, the Fed will interpret this sell-off as a run on Treasuries. The Fed is already attuned to the bond markets’ fear that there’s a “Treasury bubble”. So the Fed will open its liquidity windows, and buy up every Treasury in sight, precisely so as to maintain “asset price stability” and “calm the markets”.

The Too Big To Fail banks will play a crucial part in this game. See, the problem with the American Zombies is, they weren’t nationalized. They got the best bits of nationalization—total liquidity, suspension of accounting and regulatory rules—but they still get to act under their own volition, and in their own best interest. Hence their obscene bonuses, paid out in the teeth of their practical bankruptcy. Hence their lack of lending into the weakened economy. Hence their hoarding of bailout monies, and predatory business practices. They’ve understood that, to get that sweet bail-out money (and those yummy bonuses), they have had to play the Fed’s game and buy up Treasuries, and thereby help disguise the monetization of the fiscal debt that has been going on since the Fed began purchasing the toxic assets from their balance sheets in 2008.

But they don’t have to do what the Fed tells them, much less what the Treasury tells them. Since they weren’t really nationalized, they’re not under anyone’s thumb. They can do as they please—and they have boatloads of Treasuries on their balance sheets.

So the TBTF banks, on seeing this run on Treasuries, will add to the panic by acting in their own best interests: They will be among the first to step off Treasuries. They will be the bleeding edge of the wave.

Here the panic phase of the event begins: Asset managers—on seeing this massive Fed buy of Treasuries, and the American Zombies selling Treasuries, all of this happening within days of a largish Treasury auction—will dump their own Treasuries en masse. They will be aware how precarious the U.S. economy is, how over-indebted the government is, how U.S. Treasuries look a lot like Greek debt. They’re not stupid: Everyone is aware of the idea of a “Treasury bubble” making the rounds. A lot of people—myself included—think that the Fed, the Treasury and the American Zombies are colluding in a triangular trade in Treasury bonds, carrying out a de facto Stealth Monetization: The Treasury issues the debt to finance fiscal spending, the TBTF banks buy them, with money provided to them by the Fed.

Whether it’s true or not is actually beside the point—there is the widespread perception that that is what’s going on. In a panic, widespread perception is your trading strategy.

So when the Fed begins buying Treasuries full-blast to prop up their prices, these asset managers will all decide, “Time to get out of Dodge—now.”

Note how it will not be China or Japan who all of a sudden decide to get out of Treasuries—those two countries will actually be left holding the bag. Rather, it will be American and (depending on the time of day when the event happens) European asset managers who get out of Treasuries first. It will be a flash panic—much like the flash-crash of last May. The events I describe above will happen in a very short span of time—less than an hour, probably. But unlike the event in May, there will be no rebound.

Notice, too, that Treasuries will maintain their yields in the face of this sell-off, at least initially. Why? Because the Fed, so determined to maintain “price stability”, will at first prevent yields from widening—which is precisely why so many will decide to sell into the panic: The Bernanke Backstop won’t soothe the markets—rather, it will make it too tempting not to sell.

The first of the asset managers or TBTF banks who are out of Treasuries will look for a place to park their cash—obviously. Where will all this ready cash go?

Commodities.

By the end of that terrible day, commodites of all stripes—precious and industrial metals, oil, foodstuffs—will shoot the moon. But it will not be because ordinary citizens have lost faith in the dollar (that will happen in the days and weeks ahead)—it will happen because once Treasuries are not the sure store of value, where are all those money managers supposed to stick all these dollars? In a big old vault? Under the mattress? In euros?

Commodities: At the time of the panic, commodities will be perceived as the only sure store of value, if Treasuries are suddenly anathema to the market—just as Treasuries were perceived as the only sure store of value, once so many of the MBS’s and CMBS’s went sour in 2007 and 2008.

It won’t be commodity ETF’s, or derivatives—those will be dismissed (rightfully) as being even less safe than Treasuries. Unlike before the Fall of ’08, this go-around, people will pay attention to counterparty risk. So the run on commodities will be for actual, feel-it-’cause-it’s-there commodities. By the end of the day of this panic, commodities will have risen between 50% and 100%. By week’s end, we’re talking 150% to 250%. (My private guess is gold will be finessed, but silver will shoot up the most—to $100 an ounce within the week.)

Of course, once commodities start to balloon, that’s when ordinary citizens will get their first taste of hyperinflation. They’ll see it at the gas pumps.

If oil spikes from $74 to $150 in a day, and then to $300 in a matter of a week—perfectly possible, in the midst of a panic—the gallon of gasoline will go to, what: $10? $15? $20?

So what happens then? People—regular Main Street people—will be crazy to buy up commodities (heating oil, food, gasoline, whatever) and buy them now while they are still more-or-less affordable, rather than later, when that $15 gallon of gas shoots to $30 per gallon.

If everyone decides at roughly the same time to exchange one good—currency—for another good—commodities—what happens to the relative price of one and the relative value of the other? Easy: One soars, the other collapses.

When people freak out and begin panic-buying basic commodities, their ordinary financial assets—equities, bonds, etc.—will collapse: Everyone will be rushing to get cash, so as to turn around and buy commodities.

So immediately after the Treasury markets tank, equities will fall catastrophically, probably within the next few days following the Treasury panic. This collapse in equity prices will bring an equivalent burst in commodity prices—the second leg up, if you will.

This sell-off of assets in pursuit of commodities will be self-reinforcing: There won’t be anything to stop it. As it spills over into the everyday economy, regular people will panic and start unloading hard assets—durable goods, cars and trucks, houses—in order to get commodities, principally heating oil, gas and foodstuffs. In other words, real-world assets will not appreciate or even hold their value, when the hyperinflation comes.

This is something hyperinflationist-skeptics never quite seem to grasp: In hyperinflation, asset prices don’t skyrocket—they collapse, both nominally and in relation to consumable commodities. A $300,000 house falls to $60,000 or less, or better yet, 50 ounces of silver—because in a hyperinflationist episode, a house is worthless, whereas 50 bits of silver can actually buy you stuff you might need.

Right now, I’m guessing that sensible people who’ve read this far are dismissing me as being full of shit—or at least victim of my own imagination. These sensible people, if they deign to engage in the scenario I’ve outlined above, will argue that the government—be it the Fed or the Treasury or a combination thereof—will find a way to stem the panic in Treasuries (if there ever is one), and put a stop to hyperinflation (if such a foolish and outlandish notion ever came to pass in America).

Uh-huh: So the Government will save us, is that it? Okay, so then my question is, How?

Let’s take the Fed: How could they stop a run on Treasuries? Answer: They can’t. See, the Fed has already been shoring up Treasuries—that was their strategy in 2008—’09: Buy up toxic assets from the TBTF banks, and have them turn around and buy Treasuries instead, all the while carefully monitoring Treasuries for signs of weakness. If Treasuries now turn toxic, what’s the Fed supposed to do? Bernanke long ago ran out of ammo: He’s just waving an empty gun around. If there’s a run on Treasuries, and he starts buying them to prop them up, it’ll only give incentive to other Treasury holders to get out now while the getting’s still good. If everyone decides to get out of Treasuries, then Bernanke and the Fed can do absolutely nothing effective. They’re at the mercy of events—in fact, they have been for quite a while already. They just haven’t realized it.

Well if the Fed can’t stop this, how about the Federal government—surely they can stop this, right?

In a word, no. They certainly lack the means to prevent a run on Treasuries. And as to hyperinflation, what exactly would the Federal government do to stop it? Implement price controls? That will only give rise to a rampant black market. Put soldiers out on the street? America is too big. Squirt out more “stimulus”? Sure, pump even more currency into a rapidly hyperinflating everyday economy—right . . .

(BTW, I actually think that this last option is something the Federal government might be foolish enough to try. Some moron like Palin or Biden might well advocate this idea of helter-skelter money-printing so as to “help all hard-working Americans”. And if they carried it out, this would bring us American-made images of people using bundles of dollars to feed their chimneys. I actually don’t think that politicians are so stupid as to actually start printing money to “fight rising prices”—but hey, when it comes to stupidity, you never know how far they can go.)

In fact, the only way the Federal government might be able to ameliorate the situation is if it decided to seize control of major supermarkets and gas stations, and hand out cupon cards of some sort, for basic staples—in other words, food rationing. This might prevent riots and protect the poor, the infirm and the old—it certainly won’t change the underlying problem, which will be hyperinflation.

“This is all bloody ridiculous,” I can practically hear the hyperinflation skeptics fume. “We’re just going through what the Japanese experienced: Just like the U.S., they went into massive government stimulus—hell, they invented quantitative easing—and look what’s happened to them: Stagnation, yes—hyperinflation, no.”

That’s right: The parallels with Japan are remarkably similar—except for one key difference. Japanese sovereign debt is infinitely more stable than America’s, because in Japan, the people are savers—they own the Japanese debt. In America, the people are broke, and the Nervous Nelly banks own the debt. That’s why Japanese sovereign debt is solid, whereas American Treasuries are soap-bubble-fragile.

That’s why I think there’ll be hyperinflation in America—that bubble’s soon to pop. I’m guessing if it doesn’t happen this fall, it’ll happen next fall, without question before the end of 2011.

The question for us now—ad portas to this hyperinflationary event—is, what to do?

Neanderthal survivalists spend all their time thinking about post-Apocalypse America. The real trick, however, is to prepare for after the end of the Apocalypse.

The first thing to realize, of course, is that hyperinflation might well happen—but it will end. It won’t be a never-ending situation—America won’t end up like in some post-Apocalyptic, Mad Max: Beyond Thuderdome industrial wasteland/playground. Admittedly, that would be cool, but it’s not gonna happen—that’s just survivalist daydreams.

Instead, after a spell of hyperinflation, America will end up pretty much like it is today—only with a bad hangover. Actually, a hyperinflationist spell might be a good thing: It would finally clean out all the bad debts in the economy, the crap that the Fed and the Federal government refused to clean out when they had the chance in 2007–’09. It would break down and reset asset prices to more realistic levels—no more $12 million one-bedroom co-ops on the UES. And all in all, a hyperinflationist catastrophe might in the long run be better for the health of the U.S. economy and the morale of the American people, as opposed to a long drawn-out stagnation. Ask the Japanese if they would have preferred a couple-three really bad years, instead of Two Lost Decades, and the answer won’t be surprising. But I digress.

Like Rothschild said, “Buy when there’s blood on the streets.” The thing to do to prepare for hyperinflation would be to invest in a diversified hard-metal basket before the event—no equities, no ETF’s, no derivatives. If and when hyperinflation happens, and things get bad (and I mean really bad), take that hard-metal basket and—right in the teeth of the crisis—buy residential property, as well as equities in long-lasting industries; mining, pharma and chemicals especially, but no value-added companies, like tech, aerospace or industrials. The reason is, at the peak of hyperinflation, the most valuable assets will be dirt-cheap—especially equities—especially real estate.

I have no idea what will happen after we reach the point where $100 is no longer enough to buy a cup of coffee—but I do know that, after such a hyperinflationist period, there’ll be a “new dollar” or some such, with a few zeroes knocked off the old dollar, and things will slowly get back to a new normal. I have no idea the shape of that new normal. I wouldn’t be surprised if that new normal has a quasi or de facto dictatorship, and certainly some form of wage-and-price controls—I’d say it’s likely, but for now that’s not relevant.

What is relevant is, the current situation cannot long continue. The Global Depression we are in is being exacerbated by the very measures being used to fix it—stimulus is putting pressure on Treasuries, which are being shored up by the Fed. This obviously cannot have a happy ending. Therefore, the smart money prepares for what it believes is going to happen next.

I think we’re going to have hyperinflation. I hope I have managed to explain why.

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/guest-post-how-hyperinflation-will-happen

So my big question is, can anyone refute the logic presented here? Are our Treasuries really that toxic? Is our deflationary situation really divergent enough from Japan's Lost Decade that we could end up following in the footsteps of the Weimar Republic? Certainly this scenario is possible, but is it plausible?

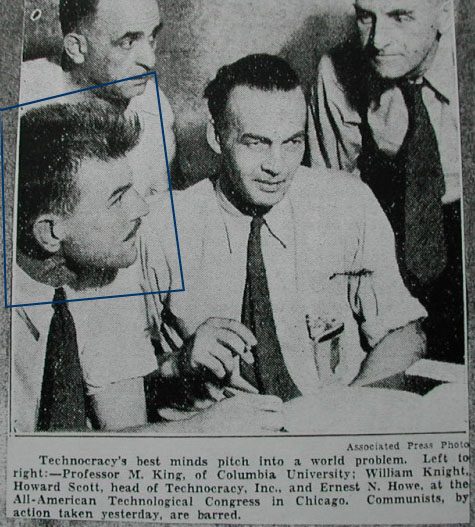

In the wake of the recent interview with Jay Hanson posted at The Oil Drum, there was some discussion of Hubbert's role in the Technocracy movement.

In the wake of the recent interview with Jay Hanson posted at The Oil Drum, there was some discussion of Hubbert's role in the Technocracy movement.